Universal jurisdiction, the only hope for prosecuting international crimes committed in Syria?

An op-ed by Jennifer Triscone*

More than ten years after the start of one of the deadliest conflicts of the 21stcentury, victims of the worst crimes have limited means to seek legal accountability and little hope that justice will one day be done. In the absence of an international body competent to prosecute these crimes, the majority of Syrian and international civil society actors have naturally turned toward the principle of universal jurisdiction. This principle allows states that recognize it to investigate and judge grave crimes committed outside their territory, without regard to the nationality of the victims or that of the perpetrators.

In the last several months, universal jurisdiction has made headlines in multiple European countries, including Germany, where a court convicted a member of Bachar al-Assad’s security apparatus. On 24 February 2021, the High Regional Court of Koblenz sentenced Eyad al-Gharib, a former member of the Syrian intelligence services, to four and a half years in prison for complicity in crimes against humanity. This was a first; in its exercise of universal jurisdiction, a foreign court sentenced a member of the Syrian security apparatus—which is still in place—and found the Assad regime guilty of crimes against humanity.

This ruling represents an important first step in the fight against impunity for crimes committed in Syria. The ruling was made possible by the courage of the victims, survivors, witnesses, and their families. The importance lies not so much in the conviction of one man but in the condemnation of a system of violence that was put in place years ago by the Assad regime. Nonetheless, we hope that this is only the beginning and that many other cases will follow.

Germany is not the only European country in which cases have been brought against members of the Syrian regime. In March and April 2021, criminal complaints were filed in France and Sweden for the Assad regime’s alleged use of chemical weapons in Eastern Ghouta in 2013 and in Khan Shaykhun in 2017. A similar complaint had previously been filed in October 2020 in Germany.

A path strewn with obstacles

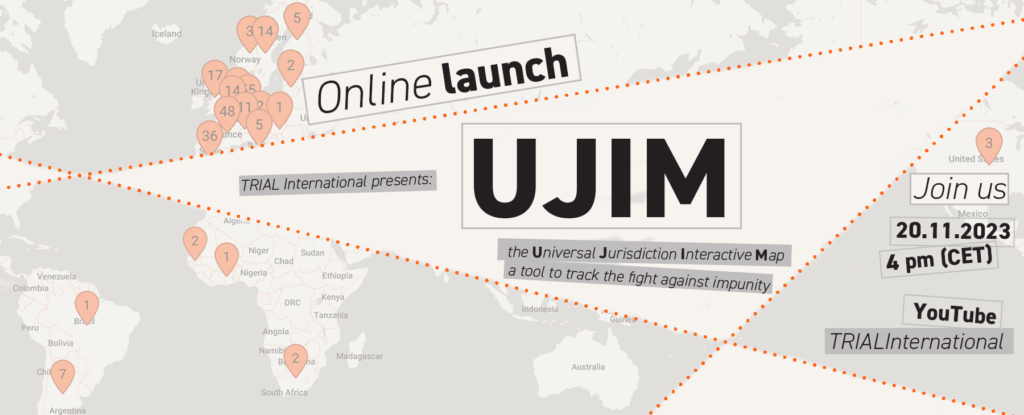

Universal jurisdiction cases are becoming increasingly common. Yet they pose challenges to the NGOs that investigate the crimes and the authorities who prosecute them. There are several reasons for this.

First, the legal framework for universal jurisdiction varies from one country to another. Although many countries limit the application of universal jurisdiction—to the perpetrator’s presence inside the country’s borders, for example—others, such as Germany, have adopted more flexible standards. However, it must be noted that despite this additional room for maneuver, the opening of cases depends in part on the will of the prosecuting authorities. Furthermore, political obstacles can arise at various stages of the investigation, particularly when the court considers whether the defendants are entitled to immunity.

The investigation itself can also prove challenging. Because the crime scene, as well as most of the witnesses and victims, may be located thousands of miles from the prosecuting court, and because certain geographic areas are difficult to access, NGOs often conduct their investigations from a distance. Building a case this way requires considerable creativity and care. The same type of difficulty arises for prosecuting authorities who do not necessarily have the ability to collaborate with law enforcement in the country where the crime occurred and who must carry out their investigation without external assistance.

Lack of funding for the investigation and prosecution of these crimes—and lack of funding for specialized war crime units in particular—is also a major challenge. Without sufficient human and financial resources, few prosecutors and judges are assigned to work on cases of international crimes. As a result, war crime units often find themselves overwhelmed by the volume of complaints they receive and have very little time to devote to each case.

Finally, safeguarding victims, survivors, and their families, as well as witnesses, is a key issue. Protective measures must be taken the moment an investigation is opened and remain in force through the duration of the proceedings. Many victims and witnesses flee their homes after the crime; those who remain often choose not to participate in the prosecution of their case because they fear retaliation, either against themselves or their loved ones. It is the responsibility of the authorities to determine, depending on the context, how to implement effective protective measures. This task is made even more complicated by the inflexibility of many legal systems, which often only allow victims and witnesses to remain anonymous when it is clear that they face concrete danger.

A platform for bringing the truth to light

The exercise of universal jurisdiction by foreign courts can have a real impact on the communities affected by the gravest crimes. The opening of criminal investigations creates a meaningful opportunity for victims of this violence to finally speak their truth and to be heard by independent, impartial authorities.

On this point, it is imperative that impacted communities be able to participate in the fight for justice. It is only by including victims and survivors in the judicial process, and by ensuring that they have access to information about trials held overseas, that a semblance of justice may one day be achieved in Syria.

These last few years, we have seen a growing number of important investigations opened involving perpetrators of international crimes. With regard to Syria, the recent conviction of Eyad al-Gharib demonstrates that it is possible to conduct and conclude these investigations within a reasonable period of time. All States that recognize the principle of universal jurisdiction must make an effort to follow Germany’s example and have the courage to exercise jurisdiction over cases of this magnitude. In particular, they must make an effort to go up the chain of command and investigate those at the highest level, without disregarding other parties to the conflict, because the appearance of judicial bias must be avoided at all costs if we want to envision one day the beginning of a transitional justice process in Syria.

*Jennifer Triscone is a Legal Advisor of the International Investigation and Litigation department (IIL) of TRIAL International and a qualified lawyer in Switzerland.